Hen Harrier

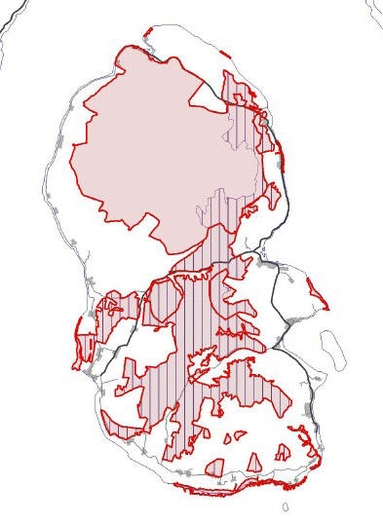

Arran is internationally important for its breeding Hen Harriers. Around five percent of the UK breeding population of Hen Harriers are found on Arran. To try to retain this, the Arran Moors Special Protection Area (SPA) and the Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), as shown in the map, were established. This area is of outstanding interest for the variety of upland habitats and breeding birds. There are large tracts of blanket bog, wet and dry heath and upland grassland. With small areas of broad-leaved woodland and several small lochs, this diversity of habitats supports a rich variety of moorland breeding birds. As well as the Hen Harrier population the area is nationally important for Red-throated Diver, Golden Eagle, Peregrine and Short-eared Owl. The knowledge of the Hen Harrier population on the island is due to the many years of effort put in by the resident member of the South Strathclyde Raptor Study Group, John Rhead.

While male Hen Harriers are a pale grey colour, females and immatures are brown with a white rump and a long, barred tail which give them the name 'ringtail'. Hen Harriers can be seen regularly from any of the roads that cross the island. They are almost owl-like in their facial appearance. The face shape helps the harriers to detect small mammals and birds concealed in vegetation, as they rely on sound as well as sight to pinpoint prey. They fly with wings held in a shallow 'V', gliding low in search of food, which mainly consists of meadow pipits and voles.

During the breeding season, males perform a spectacular tumbling and somersaulting display, diving steeply towards the ground then rearing up almost vertically before shooting downwards again. With this series of steep climbs, twists and rolls it is rightly referred to as a "sky dance". This is all to impress the females. In some areas, for example Orkney, the population exhibit a degree of polygyny, with males simultaneously raising several broods with a number of females.

It is from the end of March that the male's spectacular "sky dance" becomes frequent. The majority of males do not breed until they have their distinctive silver-grey, black and white plumage and thus are at least two years old. On the other hand, most females may breed when only one year old. Hen harriers nest on the ground, for example in areas with long heather on open moorland or rank ground vegetation in upland conifer plantations. In the south of Scotland egg laying starts during the second half of April but in cooler times it may be delayed until mid-May. The species is singled brooded but will readily replace a clutch lost early in the nesting cycle, so birds can be on eggs as late as mid-June. Clutches of four to six eggs are the norm. The thirty day incubation period normally starts after the third egg is laid but can start at any stage so that chicks in a brood can show an age difference of one or two days or up to ten days. When prey is plentiful and hunting conditions are good the majority of chicks hatched will fledge. If food is short the younger chicks in a brood die.

It is during this breeding period that another spectacular aspect of Hen Harrier behaviour can be seen, the food pass. The male supplies the female with food before and during incubation and when the young are in the nest. The male approaches with food and the female flies underneath him, turning onto her back or side and catching the prey with a foot as he drops it. The image by Maxwell Law captures the moment perfectly.

The annual breeding success is to a large extent dependent on the vole population. Vole populations in northern Europe show regular cycles of abundance, typically building to a peak every three or four years followed by a crash and a build up to the next peak. If there is a shortage of voles in an area and/or there is prolonged wet weather reducing hunting efficiency, mortality among chicks will be high. In recent years the number of young fledged on Arran has varied from around twenty to over forty depending on food availability. Fledging occurs thirty to thirty five days after hatching and the young remain dependent on their parents for a further four to eight weeks.

The presence of this very special Schedule 1 Species is a renowned feature of Arran wildlife.