Eider

With their superb plumage and distinctive, endearing calls, Eiders are a much-loved sight around the coast of Arran. In the breeding season, the male is easily identified by his pristine black and white plumage, beautifully complemented by a subtle green nape and a soft pinkish flush on his white chest feathers.By contrast, the femalewith an intricately barred pattern, ideal colours for sitting camouflaged on a nest on the ground.

The Common Eider, Somateria mollissima, is Britain’s heaviest duck, weighing between 1.5 and 2.5 kg and with a body length of up to 71 cm; it’s also the largest duck in the Northern Hemisphere.Surprisingly, it’s also the UK’s fastest duck in flight, with speeds of up to 60 mph. The scientific name of the duck is derived from Ancient Greek somatos "body" and erion "wool", and Latin mollissimus "very soft", all referring to its down feathers. The female eider lines her nest with these down feathers plucked from her breast. In Iceland, where the feathers are harvested, the contents of 85 nests will fill one duvet. Eiderdown harvesting continues and is sustainable, as it can be done after the ducklings leave the nest with no harm to the birds.

In AD 676, the colony of eiders on the Farne Islands was protected by St Cuthbert who introduced one of the first bird protection laws. The birds still bear his name:around the Northumberland coast, where they still breed in their thousands, they’re known as ‘Cuddy ducks’.

Eiders feed on crustaceans and molluscs. Mussels are their favourite food, which is why they’re often seen around mussel farms.They swallow the shellfish whole, and the shells are crushed in their stomach

Eiders are colonial breeders. They nest on coastal islands in colonies ranging in size of less than 100 to upwards of 10,000-15,000 individuals. Female eiders frequently exhibit a high degree of natal philopatry, where they return to breed on the same island where they were hatched. This can lead to a high degree of relatedness between individuals nesting on the same island, as well as the development of kin-based female social structures. This relatedness has likely played a role in the evolution of co-operative breeding behaviours amongst eiders. Examples of these behaviours include laying eggs in the nests of related individualsand crèching, where female eiders team up and share the work of rearing ducklings.Male Eiders on the other hand, while they are energetic in their display when courting, take little or no part in rearing the young.

Eiders are familiar birds around the Arran coast but their numbers are declining not only around Arran but in the Firth of Clyde as a whole.

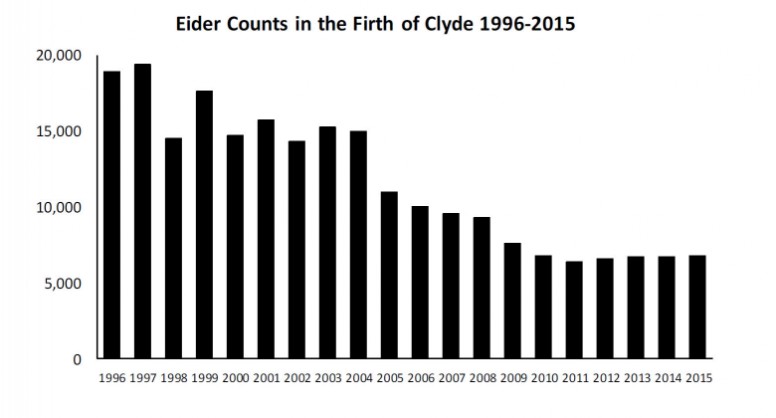

Chris Waltho, a past president of the Scottish Ornithologists Club, has organised September surveys in the Clyde for about twenty years. Chris's data above shows that the post breeding population of Eiders in the Firth of Clyde is in decline. While there appears to be some stabilisation in overall numbers since 2010, numbers have declined by more than 67% since 1997.

In the Victorian era, there was a major expansion of Eiders in western Scotland and this led to the colonisation of the Firth of Clyde, which began at the beginning of the twentieth century. With an annual population growth of around ten percent by the late 1990s, the Firth of Clyde held around 25-30% of the Scottish population.

The reason for the marked decline in recent years is not clear. The Clyde Ringing Group and Glasgow University have ringed approximately 1500 females over the last decade. These results suggest some decline in annual survival rate, but there is little evidence of mass mortality events or of any major displacement within or without of the Clyde. Mussels, crabs, starfish and other seabed creatures are the main food sources and with many different pressures and influences operating in different parts of the Firth, there is no single cause for the decline. This decline is likely to be the cumulative effect of multiple causes that have an overall chronic impact on the population.

It is important to continue to monitor the situation.of the ways that this is done is through Chris's annual survey. While the trend on Arran reflects the overall figures, there has been considerable variation in the Arran figures from over six hundred in 1999 to six in 2008. In the last four years the numbers from the Arran census in September appear to be more stable. In 2013 the total was one hundred and forty-four, in 2014 it was one hundred and sixteen, in 2015 it was one hundred and seventeen and in 2016 it was one hundred and sixteen.

For more information on the Eider I would recommend this book: The Common Eider, by Chris Waltho and John Coulson, a Poyser Monograph, published by Bloomsbury in 2015.