Common Swift

Reports

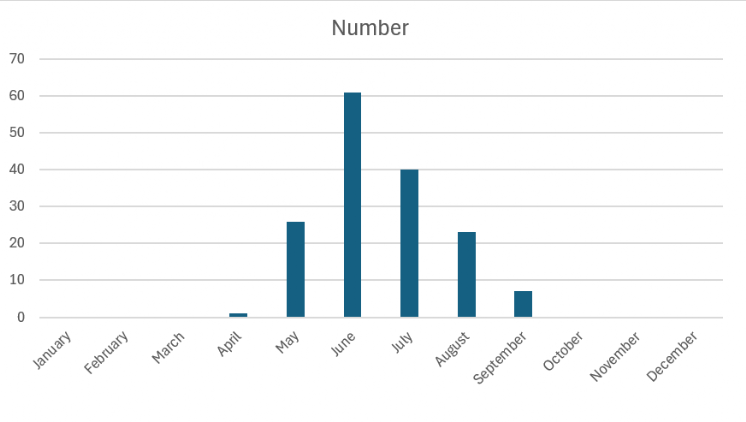

In September 2025, five reports of a single Swift were received, four from the Newton area of Lochranza and one from Whiting Bay. The Newton records were between 7th and 10th and the Whiting Bay record was on 12th. All records could have been the same bird. In twenty years as bird recorder on Arran only just over one hundred and fifty records of Swift have been received. The vast majority of these, ninety-eight, have been of a single bird. As can be seen from the graph most Swift records have been in June with only two previous records in September.

Swifts are remarkable birds. Like flying anchors, these symbols of high summer have greater mastery of the air than any other bird. Swifts drink, bathe, preen, collect food and nesting material all without landing. The night is spent on the wing and they are the only bird known to mate on the wing. They only perch in order to nest, and fly non-stop outside the breeding season, going eight or nine months without landing. Amazingly, they may spend their first two or three years, until mature, entirely aloft. Drink is taken by using the open bill to scoop water from a lake or river as the bird skims low over the surface. If by any chance they fall to earth, hampered by their short legs, they can scarcely walk and achieve take-off only with great difficulty. They never perch on wires like Swallows. Although they resemble Swallows and Martins in shape and feeding habits, the two groups are entirely unrelated and their resemblance is an instance of parallel evolution.

Swifts do not breed on Arran. However, in forays for food they range hundreds of miles from their breeding areas. They will also fly in front of and away from approaching storms. Again these journeys can be vast.

Swifts can be found throughout most of Britain and Ireland but are absent from the extreme north and west of Britain. They are commonest in the warmer and drier south and east of Britain, where aerial food is most abundant. Swifts nest almost exclusively in buildings and prefer nest sites that are five metres or more above the ground, so giving them a good opportunity to drop from the nest and gain height.

Although the Swift's stay in the UK is so short, it is a familiar bird in many of the cities and towns on the mainland. Swifts can often be found in the sky above old buildings, such as churches, where they build their minimal nests in holes in the eaves, towers and walls. Highly social, they patrol their group territories in rapid, low-level noisy flight. Parties perform high-speed aerobatics over suburban streets and gardens while making their screaming calls, filling summer evenings with drama and delight.

The Swift's stay in the UK is short, extending from early May to early August — the period coinciding with high insect populations and long hours of daylight, but with the impact of climate change that may be extending into September. Once their young can fly, Swifts have no reason to stay. They winter south of the equator. Western European populations favour Zaire and Tanzania, some as far south as Zambia and Mozambique.

The Swift is plain sooty brown, but in flight against the sky it appears black. It has long, scythe-like wings and a short, forked tail. The wings are much longer than the Swallows and Martins. On a very close view a pale throat is revealed. The Swift has a cigar-shaped body, sickle-shaped wings, and inset eyes, which have bristles to guard against damage from airborne particles.

Parent Swifts with food for their young reveal a large bulge below the beak due to a mass of insects packed into the throat pouch glued together in saliva. Detailed observations have shown that a Swift may bring 40 meals a day to their young. Eating only small airborne insects, Swifts can take thousands each day, amassing them into food balls, with which they feed their young birds. One rapidly appreciates the remarkable numbers of insects and airborne spiders consumed by a single family.

Leaving their nest, fledgling Swifts instantly take up an independent airborne life and are apparently ignored by their parents. Ringing evidence confirms that a young Swift can be hundreds of miles southwards on its first trip to central African winter quarters within 48 hours of leaving the nest. For their size they are long-lived, and individuals known to be twenty years old are on record.

If you see a Swift later in the year it might not be the Common Swift. It might be a different species of swift, the Pallid Swift, but that’s another story.